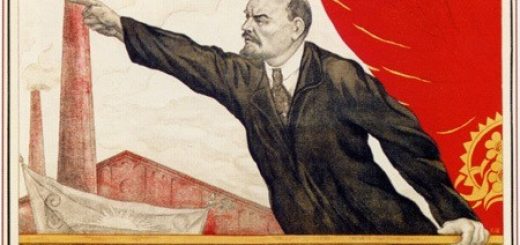

Looking for the Good Life in the Workers’ Paradise

100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution: research, collections and events at IISH.

Revolutions are about happiness, or rather, about the pursuit of happiness. Overthrowing the existing order is seen as essential for creating a better, more just and, therefore happier world. But whereas the pursuit of happiness is a universal human trait, there are a million different visions on what constitutes happiness. The happiness of the one is not necessarily the happiness of the other.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 envisaged the happiness of workers, farmers and soldiers. This was ill at odds with the image of the good life of other groups in society. In the first place, of course, of the propertied classes, who were expropriated, and often lost their lives in the process. The church also had different visions of Russia’s future, as well as the national minorities, which strove to establish their own states. It did not take long before the revolution spilt over in a bloody civil war, which raged throughout the former Russian empire between 1917 and 1922.

For the communists the revolution was part of a larger struggle. Marxist ideology hinged upon the idea of a world revolution – only if the “proletarians of the world” would unite, the revolution would succeed in getting capitalism on its knees. Everything depended on whether the Soviet experiment would succeed and sympathisers from all-over the world went to Russia to contribute to the construction of the workers’ paradise.

In the collections of the International Institute of Social History, founded in 1935 for documenting and studying the history of the labour movement, the papers of these fellow-travellers are well-represented. Henk Sneevliet (link is external), a Dutch communist active in the Dutch East Indies, visited the Soviet Union several times for the co-ordination of the world-struggle. He even functioned as a liaison for the Chinese communist party, which at that point still received its instructions from Moscow.

The Dutch engineer Sebald Rutgers (link is external), a personal friend of Lenin, took out a concession for the development of the coal-mining industry of Kemerovo in Siberia with the aid of American and other foreign communists. In his trail several other Dutch men and women dedicated to the cause came to this Autonomous Industrial Colony (AIK): the engineers Dirk Schermerhorn (link is external) (brother of the later prime minister), Gé Schoorl, Asser Baars (link is external), Koos Visch (link is external), and Anton Struik (link is external). But also the Haarlem architect Han van Loghem, who was one of the architects behind the Amsterdam social housing borough of Betondorp. Van Loghem built workers’ housing in Siberia and designed a plan for the extension of the city of Kemerovo. At the occasion of the centennial of the Russian revolution, the IISH and director Pim Zwier dedicate a documentary film to Van Loghem’s work in Kemerovo. The film is based on the letters by Van Loghem’s wife Berthe Neumeijer (link is external), written to her parents back in Holland during her stay in Siberia.

It were not just the higher-educated and professional revolutionaries who came to the worker’s paradise to do their bit: carpenters, craftsmen and even a fisherman from Katwijk followed suit and tried their luck. Particularly after 1929, when the West was in the throes of an economic crisis, the Soviet Union, with its zero unemployment, attracted many.

The curtain fell for this foreign involvement in the Soviet experiment during the 1930s, when, under Stalin, the country progressively isolated itself from the outside world. In 1927, with the start of a dedicated policy of industrialisation in the Soviet Union, the Autonomous Industrial Colony in Kemerovo was transferred back to Russian authority. Most of the foreign specialists and workers left the country again. Those that stayed on, largely perished in the purges of the late 1930s, when the pursuit of happiness in the Soviet Union degenerated into a veritable witch-hunt for everything that posed a real or imagined threat to the Soviet vision of the good life.

Only after the fall of communism Russia opened up again to the outside world. This offered opportunities for the pursuit of happiness for a new generation of fortune seekers, but also for the International Institute of Social History, which became active in Russia from the early 1990s on, in the fields of research, collection building and education, in close co-operation with Russian colleagues.

Article by Gijs Kessler

Commenti recenti